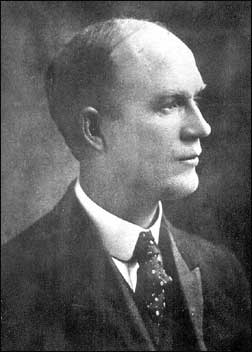

Simeon

D. Fess Simeon

D. Fess

|

|

Simeon

Fess reinvigorated Antioch

When Antioch College

students met their new president in the fall of 1906, they expected a

big man. After all, they knew Simeon D. Fess as a leading University of

Chicago scholar and a famous orator, and equated a large public stature

with a corresponding physical appearance. But they were mistaken.

“There are

those here today who recall with me a beautiful September morning in 1906

when, as a little band of students, we stood on the wooden steps at the

north entrance of the college waiting with tense anticipation to catch

the first glimpse of the new president, of whom so much had been said

and written,” Homer Corry said in a eulogy he delivered years later

at Fess’s funeral.

“The new president

came from the Horace Mann home up to the gravel walk to the College and

the inaugural ceremonies,” Corry said. “He was small, and

at first it may have seemed that this was not the man who could fulfill

the promise of rebuilding Antioch.”

At the time, Antioch

desperately needed rebuilding. Once considered at the forefront of American

higher education, Antioch had been worn down by its constant financial

struggles. At the time of Fess’s inauguration, the school had only

about 70 students and, according to Corry, “an almost hopeless outlook.”

According to a biography of Fess by John Nethers, the college’s

physical plant was badly in need of repair, its endowment held steady

at only $100,000 and revenue from students fees only reached $5,000 a

year.

But the strength

of Fess’s stature and personality immediately turned things around.

Fess’s passion

for education undoubtedly sprang from his own experiences, since education

lifted him out of a bleak childhood. Born in a log cabin in Allen County,

Ohio, Fess experienced the death of his father when Simeon was 4, and

after that witnessed the further dissolution of his family’s circumstances.

“He had seen

his father die,” wrote Fess’s son Lehr Fess. “He had

seen Squire Oles take away the only milk cow the family had, in part payment

of the tenant farmer’s rent; he had seen the kindly old country

doctor remove a battered clock from the log-hewn mantel above the smoky

fireplace as partial payment for services rendered.”

Almost sent to the

poorhouse, 7-year-old Simmy Fess was instead taken in by an aunt, then

“farmed out as a chore boy among neighboring farmers,” according

to his son. He worked summers in order to attend school during the winter,

and was such a promising student that he passed the teacher’s examination

at 19. He taught school for seven years, attending Ohio Northern University

during the summer. Upon graduation from Ohio Northern, Fess was immediately

appointed as an instructor and later became professor of history.

After receiving a

law degree, Fess became director of the Ohio Northern College of Law,

and in 1902 answered a call from the president of the University of Chicago

to help start a new university extension division. From that position,

he came to Antioch in 1906.

But why did Fess

leave a lucrative, established position to head up a college on the brink

of collapse?

“It was because

as one of the outstanding educators of that period, he had an intimate

knowledge and fine appreciation of Horace Mann and his contribution to

education and to American life,” wrote Corry. “He felt the

challenge and accepted the adventure of rebuilding a college which had

such a foundation. This decision is an index of his greatness. He was

essentially unselfish and he constantly devoted himself to causes and

institutions that were greater than the individual.”

Fess’s first

step in reinvigorating the college was instituting a summer school, with

which to attract teachers who wished, as he once had, to complete their

college degree. To further lure people to the summer school, Fess introduced

the Antioch Chautauqua, taking advantage of a popular format of the time

which featured lectures and entertainment. The Chautauqua caught fire

and remained in Yellow Springs from 1906 to about 1916.

Fess also attacked

Antioch’s financial crisis by introducing an endowment fund drive

in memory of Horace Mann, the college’s first president, seeking

a $1 donation from every school teacher in Ohio, to reach a goal of $25,000,

according to Nethers. Due to its small endowment, Antioch was on the verge

of being expelled from the Ohio College Association.

During Fess’s

10 years at Antioch, the college did show improved health. Student enrollment

increased dramatically, from an average of 50 to 70 students in the years

preceeding his tenure to 234 students in 1907 and a peak of 279 students

in 1915. He also made significant improvements to the physical plant,

including the construction of a new gymnasium

But Fess had less

success tackling the root of Antioch’s financial difficulty, its

small endowment, according to Nethers. Although his pleading letters to

other Ohio college presidents kept Antioch in the Ohio College Association,

he never did raise the $25,000 he had hoped for.

And Fess’s

efforts took a considerable personal toll, according to Lehr Fess, who

wrote that his father “struggled for years to keep Antioch alive,

but exhausted his savings and himself to the point of a nervous breakdown.”

Perhaps inspired

by Chautauqua speakers, Fess found his interest turning to politics. In

1912, he was one of three Ohio Republicans elected to the U.S. House of

Representatives and he resigned the Antioch presidency in 1916. Ten years

later he was elected to the Senate, where he spent much of his life, becoming

what Lehr Fess called an “unofficial spokesman for the Harding,

and later the Coolidge and Hoover, administrations.” At the 1928

Republican National Convention, Fess delivered the keynote address.

Although he spent

much of his time in Washington, D.C., Fess maintained his large, stately

home in Yellow Springs on the corner of Xenia Avenue and South College

Street, and he and his wife, Eva, visited frequently. Until his death

in December 1936, just after his 75th birthday — he had finally

been defeated in his Senate bid the year before, largely due to his passionate

support for Prohibition — Fess remained a local hero, his every

hometown visit generously covered by the Dayton, Springfield and Yellow

Springs papers.

Although Fess was

not able to overcome Antioch’s considerable financial difficulties,

he brought to the college a period of strong leadership, relative stability

and hopefulness.

“To Fess must

be given the credit,” wrote Nethers, “of keeping the college

alive for 10 of its most difficult years.”

—Diane

Chiddister

|